Architecture is a excellent window into the lives and minds of the people who lived in a region. While personal details are usually wiped clean upon new ownership, the balance of form and function, the nature of construction, additions and demolitions, the layout of a building and the practical issues addressed in the from of it can give a picture of the mindset and conditions in a area.

Halifax's remaining built history is very dynamic. The long history of the town, its colonial struggles, the waxing and waning with the tide of war, the tensions between our nearest neighbours and our mother country have all left their mark on our city. A blend of English, Colonial and American architecture, our built history is among the most varied on the east coast.

This page is by no means a complete list of the architectural styles which are or have been present in our province, but should give a fair overview of the major movements in the province. Not all of these styles a present in the Halifax area, Acadian and French styles being completely absent for the city's history as it was an English settlement. A French settlement had once been planned here, but was never executed. Georgian architecture marks the outset of Halifax's built history, but I thought I would add the French styles anyway to help give historical context. In theory, at least, there may have been a few Acadian style homes in the area before English settlement. Legends of places of former Acadian occupation around Chebucto were common in the early days but French censuses have lent little credence to the claims, noting only a couple of families and fishing station in the region. The French style itself helps give a picture of our great rival at the time of settlement, Louisburg.

Please keep in mind that the dates given next to each style only mark the years of prominence here, and most often approximately. Though some styles, such as French have hard set book ends due to historical facts of war, others are looser and there may be some examples which are either a bit earlier or later than others depending on a number of outside factors.

Colonial

The colonial period of our architecture is primarily defined by warfare and scarcity, leading to an architecture which was largely practical rather than ornamental like later styles. Until the end of the was of 1812 there was no security of investment in a Province which was in danger of changing hands at any moment. Lengthy wars between the French and English in which the province changed hands several times, as well as hostilities between New England and Britian combined with a inclination toward expelling your enemies from conquered territories (which the Acadians and Loyalists can both attest to) made large scale investment an uninviting idea. For much of the colonial period our largest building projects were military installations. We did, however, begin to see more construction once the often wealthy loyalists arrived and the British found themselves with only one colony left.

French 1605-1756

|

| A reconstructed French style home a Louisburg |

While no historical French architecture exists in the province today, this was a significant style of the Province through the 17th century, particularly in the French military establishments. When the first settlers came over from France they transplanted the architectural styles of their homeland. This would over the century and a half of French colonization develop into the more appropriately American style of Acadian housing.

Though not appropriate for the climate, the imported French style continued to be used in the government sponsored military settlements like that at Loiusburg. Though constructed in 1713, a century after initial colonization, the houses in this fortress appear to have been constructed in the French style according to archaeological evidence.

The French style was largely asymmetrical. The houses had steep roofs of over 45 degrees at Loiusburg, an adaptation to the snowy Cape Breton climate, but kept the french bell curve at the eaves. The frames of the houses were rectangular and the woodwork was occasionally left exposed, filled in with stone, wood or clay rather than creating a exterior layer with these materials. The houses had high walls on the first floor, but the second floor was usually absorbed into the steep pitch of the roof and expressed through asymmetrically laid out dormer windows. The other elements of the structure varied with the building materials. Stone buildings made use of heavy arches and shutters over the windows and doors, but wood and clay houses made use of basic rectangular windows and door frames. Rather uniquely the French houses had casement windows hinged at the side whereas the English preferred vertical sliding sash windows which would dominate construction after their arrival.

No original French style structures exist in the Province today, but the reconstruction at Loiusburg gives an accurate representation of the style.

Acadian ~1605-1755

|

| A reconstructed Acadian home in Annapolis Royal |

The American descendant of French style. Originally it was presumed that all Acadian houses were burned or dismantled during the expulsion, as this was the order given. But two houses were identified in Annapolis Royal, though both were heavily altered and had been absorbed into other structures. These did, however, give a great deal of information about Acadian house construction. Everything else has been gleaned from archaeological evidence.

These houses were far more functionally focused than the imported French ones, but retained the high first floor walls and steeply pitched roof. The asymmetry seems to have remained as well. Due to the means of the Acadian farmers these houses were small and made of wood, with a brick oven protruding from on side and a a small shelter of their animals on the other. The frame and mud construction of the French remained, but more often than not shingles seem to have been added to keep the relentless Nova Scotian rains from creeping in. Alternatively construction was of horizontal logs joined by dove tail joints.

Strangely, Acadian houses seem to have made heavy use of vertical sash sliding windows in the examples found. This was a distinctly English feature and may mark a certain amount of assimilation after the Treaty of Utrecht.

Georgian ~1749-1830

|

| Wentworth's Government House. |

Georgian architecture is poorly defined due to the incredibly long period which it covers, which actually spans further than the reign of the four successive George's for whom it was named, covering a period locally from about 1730 until 1830, though due to political conditions in the region one would be hard pressed to find any examples before the founding of Halifax in 1749.

The style is primarily defined as Neo-classical. Through the 18th century archaeologist in Europe where uncovering the ruins of their classical past. The most significant discovery being that of the lost city of Pompeii. Just as the discoveries in Egypt in the following century would bring about a mania for all things Egyptian, these discoveries brought about a Roman-mania, but this would go much deeper than the later manias. Art and Architecture became flooded with new classical images and ideas which had been unearthed for the first time in centuries.

Two main texts on classical architecture came out of the 18th century discoveries, but these were interpreted hundreds of times into guide books to inform the Georgia architects on how to make use of classical ideas and proportions. These served as pattern books for architects throughout the European world, and naturally found their way to the colonies across the sea.

Replacing and becoming adapted into the medieval and vernacular forms of architecture already present in the colonies, this neo-classical style became the predominate form over the next century. Though colonial styles would continue to be used in New England, which tended to be rather conservative in the pace of its style changes, these were never in heavy use here. With the late start of the 14th colony, the Georgian neo-classical movement was in full swing by the time of our founding which made it, seemingly, the exclusive choice for our buildings.

However, due to our closer proximity to New England than to Britain and with the massive influx of New Englanders into the region it appears that, at least what has remained of our architecture from this period was an American interpretation of the style rather than a direct transplant from England. This was quite natural, not only would a great deal of the architects and builders would have been from New England, but the natural resources on hand and the tenuous hold on the region would have lent themselves to wooden construction which was the domain of Colonial rather than European styles.

The same resistance to change which kept colonial forms of architecture in use in other colonies through out the 18th century would keep the Georgian style in use longer here than in Europe. Many more of houses were built by hand by craftsmen who had spent a life time learning the styles and using hand made tools designed specifically for the task and designed to last a career or more. These hard men to convince to try new things, and the style was functional and easy to assemble, which was a virtue in a war zone like the Americas. It would take until the peace and stability of the Victorian period took hold before any real change occurred here.

Georgian architecture is neo-classical in nature. The style mimics classical decoration and proportions. Though not always evident here due to materials and means, all of the architecture of this style shares these traits.

Georgian architecture is primarily characterized by classical proportions and reference. This is obvious in the large and more grand examples like the Government House and Uniake Manor, but is true in houses as humble as a town or country house. At its simplest, the style is defined by symmetry. Note the symmetrical facade of the Government House and the six chimneys place evenly on either side that enforce this. This was the ideal, but ideals and means were often far apart in a province which the Loyalist would dub "Nova Scarcity". Most of our settlers were poor, or refugees from America who could not afford or muster the raw materials for the ideal. For the most part this lead to a very small, one story house with a four bay facade and a central door and chimney, but here and in other more frugal parts of America even this had its corners cut to save the budget. Forms which became known as the "three quarter house" and the "half house" came into existence. These were exactly as they sounded, designed from the standard four bay but stopped at the three quarter mark of the third window or at the half mark of the door. Everything else remained the same, leading to an uncharacteristically asymmetrical design based on the same classical proportions.

|

| The Samuel Greenwood House in Dartmouth is an example of a Georgian half house which was common for the region due to space and economic concerns. |

Decoration was often limited here, again due to means. However, even at its grandest, decorative elements such as mouldings were delicate and understated. Window frames tended tobe crisp and unadorned, generally no more than rectangular hollows without framework. Dentil mouldings were the standard when more than the basic squared mouldings were used. Over doors transom lights (a narrow march of little window panes across the top of the door) were almost always present though the scale was dependant on the wealth of the owner. On the grander buildings where stonework and arched frames could be afforded fan lights (the same idea but in a fan shape) were preferred. Roman columns were almost always a must, and were worked into the frame work around doors or side boards at corners were exaggerated to resemble them on the less well to do homes. On more extravagant houses the columns were separated from the main frame to form a pediment designed to look like a Roman temple.

The style makes heavy use of the various orders of classical columns, which the Renaissance archaeologists and architects defined as Doric, Ionic, Corinthian and Composite. Each had its own style and proportions as described by these Renaissance scholars. These proportions were carried into the rest of the structure, essentially defining (in the structures which had been afforded full columns) the whole layout by the columns. Each one tended become a standard for specific types of structures they were most suited to. Proportion was very important to the style. Everything was worked out to balance visually with the proportions of the columns and each other part of the building. Just the Government house to see this. It is balanced on the side by two wings which are a story shorter, each floor of the main structure are visually separated and each column of windows is visually serrated by an engaged column. On Georgian structures there is a strong focus on the horizontal, as opposed to the vertically of Gothic and later Victorian forms. To achieve this, each floor is clearly set out in these houses, separated by visual lines, and by a rustication of the bottom level. Rustication is a purposeful exaggeration of the gaps in the masonry which in Georgian buildings gives a very heavy feeling to the first floor and draws the eye down, encouraging that horizontal emphasis. The buildings are long and give a stout profile even while being several stories tall. Notice how the government house has strong rustication which brings focus to the first floor, has wings to lengthen the horizontal profile of the home and has a shortened third floor to dampen its vertical impact.

|

| The Loyalists brought many New England variations of Georgian architecture directly to the province, such as the Akin house which is a Cape Cod variation of which there are a few others in the region. |

Georgian style, being so long lived and wide spread, realistically defines a multitude of styles simplified under one umbrella. Scottish, New England Salt Box, Palladian, Nantucket, Colonial, Federal, Regency and many others identifiable styles fall under the Georgian umbrella. The style is therefore problematic, but is not the less used to define much architecture. The style is defined less by individual elements, or even a time period, but rather by an ideal which all these structures strove for.

The style is essentially the founding style of the colony in Nova Scotia since the English went to such lengths to dismantle and burn the French and Acadian structures. Due to the age and the rather bleak state of the colony during the Georgian period, few structures from this period and style exist in the province today, but there are enough to give us a strong sense of its local expression.

|

| St Paul's is a rare example of a Georgian Church in the area and is also the oldest remaining structure in Halifax. |

This is one of two of the main styles of ecclesiastical architecture which can be found in our province, the other, which is much more prominent now, is Gothic Revival. Georgian churches were made to echo Roman basilicas and temples. These churches run the gambit from as iconic as the round churches, such as St. George's to the Gothic-like steepled churches like St. Paul's or Christ Church. In both cases these churches are easily identified by their round arch windows which are distinct from the pointed arches of their Gothic cousins.

Scottish ~1790-1840

| A Scottish style house in Port Hood |

While technically Neo-classical or Georgian, this is a while defined subtype from a particular region making it easy to discuss in its own right.

As the name implies, this style was brought to Nova Scotia by the Scottish immigrants who began arriving in the latter part of the 18th century to areas primarily in the North Western part of the colony in areas still identifiable Scottish such as Pictou and Antigonish.

The style made heavy use of symmetry, even more so than other Georgian styles, and the proportions were neo-classical but the two features that mark this style as unique are the dormers and the raise gable walls. The "Scottish Dormer" is a five sided dormer which creates an interesting silhouette compared to the standard dormer. These Scottish Dormers however are troublesome in Nova Scotia, being so popular that they were added to many pre-existing Georgian buildings given a misleading sense of style and ancestry.

The other significant feature, the raised gable wall, is more specific to house of Scottish construction. This feature was a direct carry over from the home country. Scottish style homes invariably have an gable roof flanked by two walls which extend over the height of the roof. Each of these flanking walls has a chimney protruding from it which gives a pleasing sense of symmetry. Because of the universal use of dormer windows and a gable roof, these houses are almost always 1 and 1/2 stories tall. Other than these details mentioned above the Scottish style home is largely identical to Georgian houses, though they favoured retaining their symmetrical facades rather than being reduced to three quarter and half houses.

While there is evidence of Scottish style homes being built in the Halifax area, few if any have survived. This presence is mainly felt here in its strong influence on the Halifax House style discussed further on.

Quaker 1785-1792

|

| The Last Quaker House in Nova Scotia. It has been renovated in the back and has lost its slat box roof. |

Quaker housing is a specific form of the New England Saltbox. Both are part of the North American vernacular tradition. These houses were the practical applications of Georgian style architecture to the North American climate. The saltbox house is largely identical to other two story wooden houses of Georgian style, but their gable roof extends down to the first level, creating a house which is two stories on one side and one on the other. This made a silhouette which resembled the boxes used to store salt through the 17th and 18th century, which is how the style got its name. This style is one of the early examples of distinctly colonial architecture.

Quaker housing is a peculiar cultural and regional adaptation of the saltbox style. Uncharacteristic of the time this style is asymmetrical, both due to the salt box roof and the odd number of bays the builders used on the facade. The door is also shifted to an asymmetrical position. The style was common in Quaker communities which were largely focused on Nantucket Island in New England. There is only one remaining house of this style, though nearly all of the settlement of Dartmouth was populated with these house at the end of the 18th century. These were constructed by immigrants from Nantucket Island and the style never spread beyond the town of Dartmouth where they settled for 6 years.

Victorian

The close of the Nepoleoic wars in 1820 brought Nova Scotia its first taste of peace since the early days of colonization. Since the founding of the city, Halifax's mainstay had been warfare and the sudden and unexpectedly long dry spell brought a need for diversification in economy and industry, and the prolonged peace encouraged large scale investment around the province.

The prosperity of peace hit is stride in the Victorian period, commencing with the crowning of the new Queen in 1837. The Nova Scotians of this period were proud, industrious, fiercely independent and innovative. Their lofty goals were often marked in the grand architectural projects and styles of the period.

Victorian culture was a marked change from the colonial styles which preceded it. The stability and wealth of the day encouraged more grandiose projects more on scale with Europe, but the prevailing culture did as well. Notoriously ostentatious, the Victorians were obsessive about blending the practical and the beautiful, which is why Gothic revival did so well here. The Georgians before them, particularly in the colonies had been practical almost to a fault. The Victorians drew from new sources and melded form and function into an incredible new styles, and created a complex architectural legacy like nothing before it in the English world.

Greek or Classical Revival~ 1820-1860

|

| The Caldwell-Hill House is one of the best and most literal examples of Greek Revival in the region. |

A second wave of classical revival which began in North America as part of a conscious effort by the newly formed America to separate itself from its colonial past, though the styles roots come from the same British classical revival that the Georgian style was born out of.

The style caught on in Nova Scotia much later than elsewhere on the continent, and it was muddled up with the previous more Roman revival, partially to temper the style too make it less reminiscent of the American style which would come off as too revolutionary. In general the remaining British colonies, where the Loyalists who had been so rudely removed by the revolutionaries, were distrusting of anything related to republican politics like this style. It was further dampened by the poor economy of the province during the peaceful years of its development which stifled construction.

The style is only represented by a few very examples scattered across the province. The style is marked by ionic pillars, and pure white paint meant to echo the Greek marble. The style is generally meant to echo a Greek temple. Some houses, like the Caldwell-hill house in Halifax which has a wrap around veranda with ionic pillars. Most simply make use of these as a temple facade over the entrance. The corners often had exaggerated pilasters, similar to Georgian but more prominent, which helped re-enforce the classical theme.

Commonly, the top floor of gabled homes of this style have a visually separated top floor reminiscent of the top of a Parthenon style temple. The doorways were square and recessed. The windows were capped with mouldings which were raised above and separated from the window frame. The window mouldings are very simple.

All in all, here in Nova Scotia the style is not very distinct from Georgian neo-classical. The proportions were similar though tended to be more authentic (in the beginning). The corner pilasters were much more prominent than in the preceding style and raise to a pediment roof. The translations of classic influence were often more literal than in Georgian.

Gothic Revival ~1830-1890

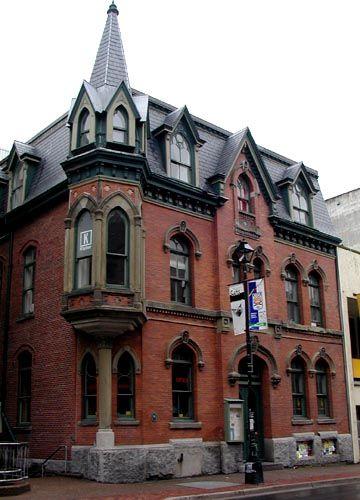

|

| The Kyber Club is one off Halifax's rare examples of Gothic Architecture. Like most in the city, it was an ecclesiastical building, which were the style was expressed in its grandest forms. |

The style is characterized by its pointed arches and steeply pitched roofs which were meant to echo the verticality of high medieval architecture. As the steep pitch of the roofs made them well suited to shedding the heavy snow and rain of Nova Scotia the style quite naturally became the most popular in Nova Scotia, despite our refusal to build with the proper stone materials. The notable exception to this is Halifax where the style is exceptionally rare. Halifax was much too conservative in its tastes and obsessed with the upper crust of British Society who still favoured the classical revivals. Primarily Gothic Revival is seen in churches here. However, all through the rural counties of the province you will find many examples of these houses today.

The style apparently originated as a whimsical move of architects who bored of the rigid and plain architecture of the classical revival movements which dominated the previous century. The style got its birth when architects began to add point arch windows reminiscent of Gothic churches onto neo classical buildings. Once the style took on an existence of its own, the pointed arches remained the hallmark feature of the style. Curved wood was the preference for forming these, but when the funds were not there straight boards forming a triangular cap to create the appearance of an arch. The arched windows varied in complexity, some containing decorative rosettes which made them look as if they were transplanted from a Gothic church rather than made for a home.

The writers of the pattern books had in time accepted that the North Americans were not going to change their minds on wood construction and began to set out rules on the style of construction which would be true to the revival. Aside from the stone like paint purposed above, they suggested vertical board and batten siding. This however was rarely used here where clapboard and shingles were still preferred.

Bargeboard, finial and pendant ornamentation added the lightness that the revival style was initially missing in comparison to its parent style. Finial ornaments were turned wood decorations fixed to the peaks of the roof and projecting above it, were as pendants hung below. The very complex and multi peaked houses of the late Gothic Revival make heavy use of these. Bargeboards were another decoration of the roof, being a board cut into lace like patterns and hung under the eaves. Again, this was almost essential to late revival homes.

|

| The Oakland Cottage on Robie St is an example of a Gothic Revival house with bargeboard decoration. |

The most common form of Gothic Revival house in Nova Scotia was a simple gable house with a prominent point on the front which was essentially an exaggerated dormer. In the space afforded by this dormer there would always be a pointed arch window which would often be the only one on the house. It served as a stylistic centerpiece above the front door. The rest of the house was unremarkable, a simple two bay facade otherwise, much like an small Georgian home, but the steep pitch of the roof differentiated it. Many of these would have had bargeboards, but a good number of these have been removed.

|

| The Morrison House of St. George's Channel is an example of the most common for of Gothic home in Nova Scotia, though with a side addition on the left. |

|

| St Mary's Basilica is perhaps the crowing example of Gothic Revival architecture in Province. |

This style found its full expression in ecclesiastical architecture. The churches of this style are characterized by their high, pointed steeples, steeply pitched roofs, arched windows, buttresses and projecting finial. The range of expression is from the single room, steepled churches of Annapolis Valley, to the larger examples like St James in Dartmouth up to our crowning example of St. Mary's Basilica in Halifax.

Italianate ~1850-1890

|

| True Italianate is rare here, muddled Georgian homes such as the Benjamin Weir House are more commonly the expression of this style. |

This style was inspired by the architecture of Renaissance Italy, which itself was a classical Roman revival. The style echoed Italian villas of this time and consequently was rather ill suited to the climate of the province, which likely contributed to the eventual development of the sub-style of Bracketted houses which was far more popular. This style, being another European import, was translated into wood from stucco and stone.

The style was more inventive, more creative than the previous revivals, in its way. The subject matter that Italianate architects were drawing influence from was a more liberal and creative interpretation of the classical style of Rome. Many of the details of the details of the Italianate style were new to Nova Scotia, such as The heavy gables overhanging the rest of the house, which in the Renaissance style that was being copied were to shade from the bright Mediterranean style. These and the brackets supporting them were distinct from the previous century, more closely resembling the Gothic Revival movement than anything else.

This style favoured porches, storm or otherwise, usually complete with a balustrade above. In Nova Scotia, due to the harshness of the weather, storm porches were the more common than those of the open kind. These storm porches provided a barrier against the muck, wet weather and cold. Storm porches of this style were usually a modified form of a palladian window (a tri-arched window from the Georgian period) and added an element of complexity to the style. Many of the larger examples have a belvedere (a small enclosure on the roof top), usually complete with a "widows walk", a roof top balustrade which takes it colloquial name as a place where a wife could vainly survey the water for her shipwrecked husband.

The forms expressed by this style are quite varied. These range from a gable roof home with a five bay facade that looks very much like a Georgian home but with a balustrade, to the grand houses complete with pediments, columns, projected bays and windows capped with ornate brackets. Identifying this style can be problematic at times however as it shares a good many traits with several other styles.

Bracketted ~1850-1890

A more partical adaptation of the Italianate style.

Second Empire ~1855-1900

|

| Victoria Hall on Gottigen St is one of a few examples of "pure" Second Empire in the city. |

This style is one of the more lavish forms to come out of the Victorian period, though unlike the other styles of the day it was not brought over from Britain or up from the United States but rather it came from France. The popular international exhibitions held in Paris through the mid 19th century brought the building projects of Napoleon III and Second Empire France to the attention of the British and North Americans. The style we see here is a translation of the Parisian one, again translated to wood.

The whole style hinges on the extravagant Mansard roof, a creation of Francois Mansart, an early 17th century French Architect. It is both the most recognizable part of these homes and the focal point from which much of the rest of the styles features stem. Often the amount of complexity in this roof marks the age of the home, though not always.

The Mansard roof is two tiered. In its purest form, the peak is a hipped gable roof, a shallow pyramid form which hinges into a steeper bell curved lower tier which falls over the entire second story. This necessitated the use of dormer windows. In Europe the Mansard roof would have been shingled with slate of various colours. Though a few homes here were built this way, almost all such homes had this element removed in subsequent repairs. Most commonly wood shingles were used here, often cut into different shapes and patterns to give the visual flare the monochromatic wood couldn't give on its own. We also made use of very ornate molding below the eaves to make up for this same dullness of the wooden architecture. Originally the hing of the roof would have been crown with a wrought iron balustrade but for the majority of homes these have long since been lost to corrosion.

The other elements of the style are strongly reminiscent of Italianate or Neo-classical forms. The eaves were supported by large ornate brackets similar to Italianate houses, and its projected bays and storm porch additions closely resembled this style as well. The rest of the decoration tended to involve the use of Georgian dentil mouldings and pilasters. Rounded dormers, window cornices and doorways giving the appearance of classical arches were the standard, but in the local translation to wood this was sometimes dropped in favour of the easier

This style was well suited for large public buildings and was often used as such. Schools, Academies, the North End train station as well as various Hotels and Inns were constructed in this style. While it worked best for these larger buildings, it was altered by local architects and made versatile enough for virtually any size or budget. This often required adaptations to the Mansard roof which was a very costly element. Some homes dropped the bell curve bottom tier in favour of a flat either vertical or very steeply pitched tier. Even more common were houses which had a facade of a the tier in which the curve only fell over the front and back, and the really scaled down, only the front in order to give the appearance of a Mansard roof from the front. On these smaller versions the rounded cornices were often dropped, though the rounded dormers were often retained. Where they were not pediment caps were the cost effect style of choice.

Larger structures of this style, and many larger houses, had a central tower capped with a miniature Mansard roof and dormers. This tower would rise about a story above the rest of the building. Some of the mid range houses had an engaged tower but this did not extend beyond the second level. It did, however, maintain the pleasing sense of symmetry the tower lent to houses of this style. The lowest floor of this tower provided the space for a foyer to keep the outside world and the interior at arms reach. It is only the smallest Second Empire houses which are asymmetrical for cost reason. The tended to have storm porches of Italianate style which served the same functional purpose as the foyer.

|

| An example of a Georgian style home with a Mansard addition. |

This style became less distinct as the Mansard roof became a popular way to renew and modernize older homes. These renovated versions are often quite obviously out of place however, and are usually placed on to distinctly Georgian buildings.

|

| Small scale Second Empire houses with partial Mansard roofs are most common in the Halifax Region. |

Halifax, as with many styles in the Victorian Period tended to use these more ornate styles on public buildings. Being an urban area, we had fewer examples of the grand country homes that other parts the province have. Space and ready reproduction were concerns through this boom period for the area, and so in most cases you will see scaled down versions with inspiration drawn from the Second Empire style.

Late Victorian Styles

The latter part of the Victorian period through the relatively short Edwardian Period were a stylistic melting pot. The styles that arose in this period are not easily differentiated from each other as they often cross influenced and took inspiration from the same revivals. This was period of great creativity, spurred on by improve technology which made more elaborate forms more affordable and easily reproduced. The styles were also affected on the same lines by the improvements of the continental rail systems which made materials cheaper and more accessible, and began the movement of prefabricated, mail order houses and additions.

The scope of the revivals that had begun way back in the 17th century with Georgian Neo-classical had expanded to an eclectic and ostentation grab bag of revivals mashed together and displayed side by side, not always in a congruent fashion. This far reaching trend in architecture came to envelop every English style from High Gothic through to the Victorian styles themselves.

Queen Anne Revival ~1880-1915

|

| The Wright House, now owned by the Council of Women, is probably the city's most grandious example of Queen Anne Revival, though it is muddled with a few other styles. |

This style is a late 19th century revival of a relatively short lived style from the 17th century reign of Queen Anne. The style was a English adaptation of the Dutch architecture the royal family had been surrounded by during their exile. The style developed at home combined red brick structures framed with white moulding. The origins are difficult to trace in the 19th century revival which is more often than not mixed up in other styles, seemingly lacking the definition to hold its own. This often barely distinguishable from Victorian Eclectic. The style was an eclectic combination of neo-classical, Gothic, medieval, Tudor, Elizabethan, Jacobean, Arts and Crafts and many Victorian styles. It was a hodgepodge of virtually every English style before it and contemporary to it.

Queen Anne is one of the most complex, gaudiest and least cohesive styles of the period but there are a handful pf commonalities between the otherwise rather unique expressions of the style. Contrast; whether in texture, form, colour or most often a combination of the three, is the key to Queen Anne. The style's main feature are the prominent gable end (or ends), which is the showpiece of homes of this style. It is always segmented to form a full triangular pediment. Often the gable contained an ornate palladian window (a three bay shape window with a larger central arch) though this is sometimes reduced to a simple three bay window or a single arch. The gables often made use of many different shaped shingles to create a rather gaudy display. Most of the time this gable end has a Palladian window, which are another common feature of the house in general. The style is always asymmetric and often, particularly in larger examples, is irregularly shaped. Queen Anne houses often have a tower, usually round but sometimes polygonal, which rises along with the usually hipped central roof, the cross gables of the pediments to create a dramatic roof scape which is suppose to be reminiscent of medieval buildings. There is usually a veranda on this style of home.

The shaping of shingles into a multitude of patterns was popularized by the Queen Anne Revivalists. Bands of alternating patterns ran up the structure. This feature has rarely survived through the years of renovations and the later popularity of vinyl siding which could not replicate the complexity. This has caused many houses style to lose much of their defining character.

|

| Due to lot sizes, the house on the far right is much more exemplary of Halifax's expression of the Queen Anne style. Note the prominence of the third floor gable end. This marks the local homes of this style. |

The style exists in several very loose modes. Free classic, which is heavily reliant on Neo-classical elements. There is also Spindlework which makes a gaudy display of various forms of wooden ornamentation. Half timber uses more Tudor like exposed beams. There is also a Masonry mode which is rather self-explanatory but very rare, as all stone architecture is, in Nova Scotia.

Free classic is probably the most common mode in the province. The Wright House, pictured above, is one of the grandest examples of it. The pediment gable end is the centerpiece of the house and caps off two neo-classical columns to create the Georgian temple facade. The uses of classical columns and Georgian features combined with decorative gable ends ans irregular asymmetric shapes which do not fit with the neo-classic are the hallmarks of this style, which can sometimes make it difficult to identify in this mode. This particular example is a bit different since it is a combination of Half Timber and Free Classic. The Palladian window is shifted down to below the gable in order to allow for the Tudor-esque half timber decoration. The characteristic round tower is present in this case.

Spindle work mode is very similar to the Stick style and several other contemporary styles, leading to difficulty in identification. Again, asymmetry, a tower, irregular form and a prominent gable end are the key to differentiation. The gaudiest of the modes, this makes use of several Gothic features such as bargeboards, finial and pendant ornamentation. The style also makes use of very decorative and exaggerated brackets from the Italianate and projecting timber features hanging below the eaves which were essential to the stick style. In the spindlework mode of Queen Anne the gaps in the timbering were filled with a ostentatious display of turned or cut elements. As is common for Queen Anne these elements were painted an array of contrasting colours to increase the visual impact. Verandas in all modes, but most often for this one, make use of intricate designs of curved timbering not seen in other styles.

Much of what was characteristic to Queen Anne, particularly for spindlework, was due to technological advances, rather counter intuitively considering how caught up the style was in the anti-industrial Arts and Crafts movement. The shaped shingles, curved timbering, turned wood, and etc were rendered cheap enough for mass implementation onto a home because of advances in steam power and woodworking machinery such as the rip saw. All these elements were possible before but too labour intensive for mass use. As with everything in the Arts and Crafts movement the celebration was of handcrafts and unique pieces, but in practice all the hand crafted items were mass produced and often machine made.

Masonry mode, being stone construction, is virtually non-existant in North America and even more scarce here. The style has no unique features compared to the other modes except, as the name implies, that it makes use of stone and brick to create the contrasting colours and textures required by the style. The stone and brick are often carved or placed in jutting patterns in varying protrusions along the edges of the home and under the eaves and at the mouldings to echo the textures and designs present in the Spindlework mode.

Half timber style is even more uncommon, and other than the mingled Free Classic version of this which is present in the Wright house I know of no local examples of this style, which is simply a Queen Anne home making use of half timberig rather than shingle work to create its characteristic contrast.

Stick- ~1880-1910

|

| The Chase Inn of Wolfville is a wonderful example of the Stick style. A seemingly rural style, it is incredibly rare in Halifax where Queen Anne was favoured. |

The style makes use of finial, pedant, bargeboard and balustrade decoration on and almost absurd scale, and in many creative forms rarely seen in its cousin styles. The characteristic woodwork of Stick is applied rather undiscerningly over frames of various or eclectic origins. Usually the style makes use of horizontal, vertical and sometimes diagonal boards as siding (most often combination), using shingles sparingly and as accent, giving it distinction from its Queen Anne cousin.

The style was favoured across North America as a cottage style, and along the ever expanding railway network with which it became associated. This makes it a a largely rural and frontier style, perhaps explaining its rarity in the largely settled Nova Scotia, as well as its notable popularity in the town of Truro, the rail hub of the Province.

Shingle

French Romanesque Revival

Late Victorian Eclectic

Late Victorian Plain

Victorian Interiors

Regional

Halifax House

Lunenburg Bump House

Modern

Arts and Crafts Bungalow

Hydrostone

World War II Prefabricated

Anyone seeking more information on the Architecture of Nova Scotia should look to Allen Penney's Houses of Nova Scotia which is widely held as the best reference on the topic. Heritage Houses of Nova Scotia by Stephen Archibald and Sheila Stevenson is another great refrence on the topic.

All photos are taken from Historicplaces.ca.

2 comments:

Nice blogpost, having very good details about Shingle Style Homes.

Thanks for sharing.

French country custom home design

The Nova Scotia Association of Architects book Exploring Halifax 1 ed.George Rogers [Formac Pblg 1984] @pg 39 records 5693 Victoria Rd(sic visibly echoed on the block for three more adjacent houses):"The mansard roof is the distinguishing feature of this Second Empire house.Note the bracketed eaves and s mallMansards over the porch and dormers..steeply sloping roof with a flat or shallow pitched top is most noticeable.Dormer windows with rounded tops are built into the slope and the door often has a cornice moulding with an upward curving centre.The roof slope is a flat plane,which develops into a double curve and may even have an extra cornice moulding added half-way up the slope.The roof edge cornice of many houses is positioned high by lengthening the walls;it gives them a more grand outside appearance."

Post a Comment